Khaborwala online desk

Published: 08 Feb 2026, 03:52 pm

Fourteen years of widowhood have passed.

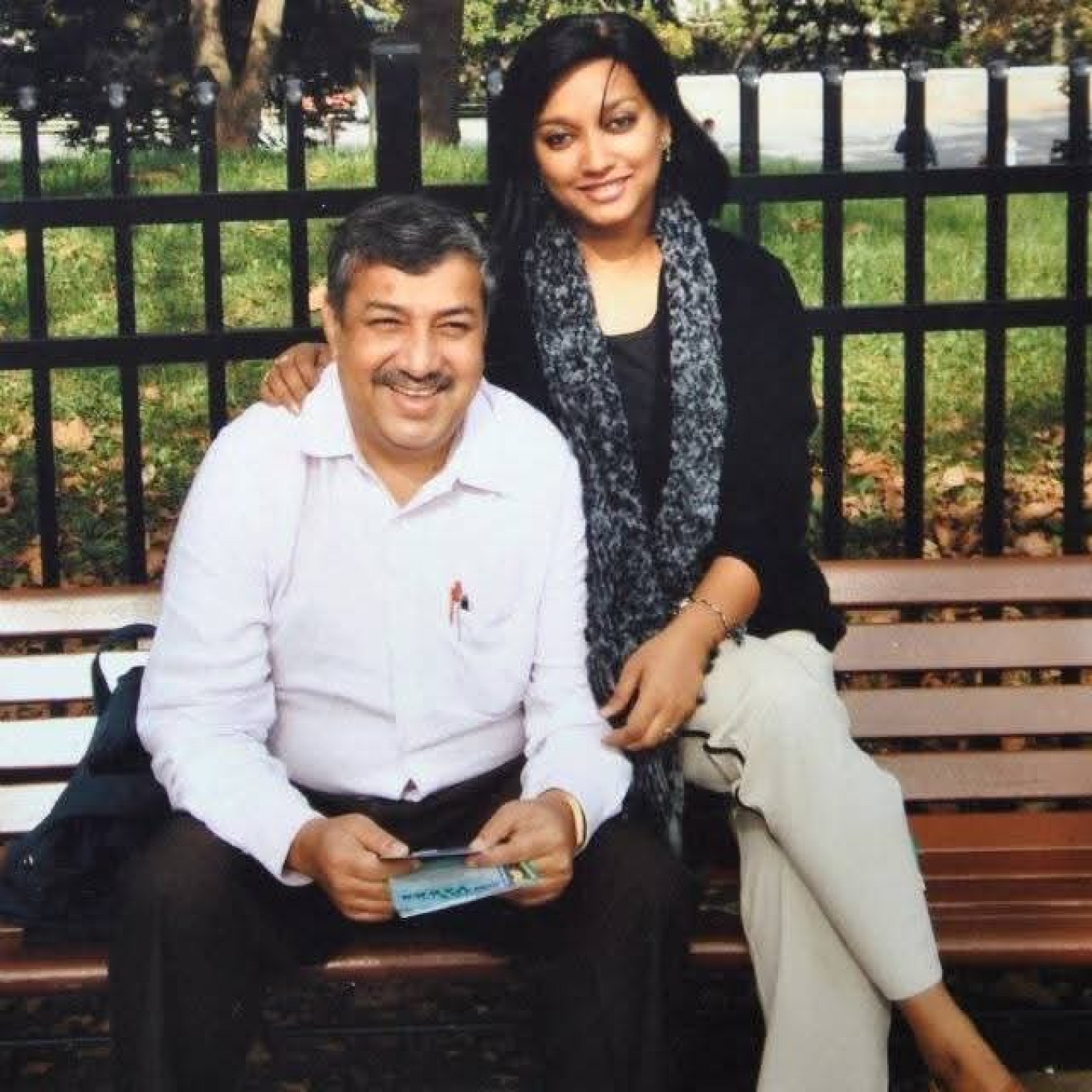

I am exhausted from seeing so many kinds of people, from glimpsing faces hidden behind masks. Watching the inhumanity, arrogance, ego, pettiness and vindictiveness of so-called great people, I often feel that Jahangir Sattar Tinku truly was a compassionate, genuinely great human being.

At last, he left. It was 4 a.m. at dawn. I was sitting there, holding his hand. His body had become terribly still. The doctor came and said he would be taken to the ICU. I said there was no need. Let him go. With pain spread throughout his body and a chest full of unspoken grievance, he slipped away. For fifteen months I had been preparing myself inwardly for this moment. And yet, how strange it was — all my preparations were swept aside and my heart broke into a wail. The shock was so severe that I felt utterly alone in this world. Pain upon pain. I could not bear it any longer; I went into the bathroom and cried out loudly. Had he really gone? Leaving me alone? What would happen to me now? What of the countless memories of eighteen years? What of the many dreams we shared? It was as though our life had come to a halt halfway through.

His lifeless body lay on the bed, covered with a white sheet. I could not look at him. Consciously, I turned my face away. I could not accept his condition. I resolved that I would not look at him again. I sat there. If life is merely breathing in and out, then I was alive. Tears of pain streamed down from my eyes.

Exactly fifteen months earlier, on 10 November (the day was Tinku’s birthday), a tumour was discovered in his brain. My doctor brother tried to prepare me, saying chemotherapy or radiotherapy might be needed. I asked, “Malignant?” He said, “It could be.” I was stunned. The world seemed to sway above my head. Darkness closed in before my eyes.

After surgery at Gleneagles Hospital in Singapore on 13 November, Dr Trimothili told him, “You have glioblastoma, grade four, multiform type tumour — one of the most aggressive forms of cancer.” I was holding Tinku’s hand. Wearing an oxygen mask, he began to cry. I knew I could not afford to be soft — he would collapse. I tried to speak lightly: “This is normal for you. Everything about you is uncommon — your blood group, your intellect, your appearance, your intelligence. How could you think you would have an ordinary illness?” Even in pain, he tried to smile.

After a second operation on the 16th, the doctor smiled and said the surgery had gone very well. Tinku said, “I’m fine.” I was overjoyed. I rushed to Arab Street and bought three lace saris from Royal. When the shopkeeper said, “Madam buys saris from our shop,” I bought another French chiffon as well.

Five days later, the radiologist came to see him. With a smiling face, Tinku asked, “Doctor, how long do I have to live?”

“Five years,” the doctor replied.

A shadow crossed his face. I thought to myself, only five years — and so much of our life still remains, so many words, so much longing. I did not yet know how much more there was for me to learn.

While shopping at FairPrice in City Square Mall, Tinku’s friend Nafis called and said, “Munin, there’s no hope. I’ve searched the internet thoroughly — eight to twelve months.” My legs felt numb. I sat down on the floor. From then on, whispers of “eight to twelve” echoed everywhere. I began to decay from within.

Tinku said to me, “You married a man who has no lifespan.”

“What will happen, Munin? You’ll become a widow at such a young age.”

I hugged him and burst into tears. We cried together.

We rented a large flat at City Square Residence and brought a cook from home. Our picnics began. Every week, two of Tinku’s friends came from Bangladesh. Others came constantly from Australia, Malaysia, Singapore and many parts of the world to offer prayers and condolences. Our four-bedroom flat was always full. Seeing Tinku’s fortune in friends, I felt a twinge of envy.

After the first round of chemotherapy and radiotherapy, three months later, we returned home in February. Five days later, we left for MD Anderson in Houston. Houston is a quiet, orderly city. Every time I come to America, I feel how much empty space there is. I wonder what would happen if we brought some people from our country here.

At MD Anderson, an impossibly smart and beautiful oncologist told Tinku, “Fifteen months.” We both broke down in tears. We decided to focus on spending quality time together. Twenty days later, we returned home, carrying a chest full of despair. Everyone said, “Go for Umrah.” In March 2011, we went to Saudi Arabia. After that, blessed water, prayers and talismans became our constant companions.

During tawaf, at one point I was overwhelmed with emotion.

“O Allah, You know everything within me and beyond me. You know even what I do not. Whatever is written in my fate will surely happen. Grant me the strength to endure it.”

My eyes filled with tears.

Every month he travelled to Singapore with Popsi Bhai, a doctor and one of his closest friends. I did not want to go — I was afraid. In July and August, two more surgeries were performed: one on the skull, the other gamma knife surgery. There was no alternative. New growths had appeared in three places.

The last time, after Eid al-Adha, when he went to Singapore, instead of saying hello on the phone, there was only the sound of sobbing. I understood everything. I simply said, “Come back to me.” Within two days, his right leg became paralysed.

I said to him, “I’ve had a wish for a long time — that we would eat from the same plate. From now on I will feed you, bathe you, shave your beard, put on a different perfume every day, comb your hair. I’ll do all this for my own happiness. I will always be with you.”

Tinku was immensely happy.

He was extremely sociable, unable to stay without people even for a moment. He disliked staying indoors. I bought a wheelchair for him. I am a member of four clubs in Dhaka, including Dhaka Club and Uttara Club. Only then did I realise that, apart from clubs, there were no proper wheelchair facilities in government institutions, shopping centres, five-star hotels, community centres or important establishments. Does that mean we will never grow old? Or that the elderly have no right to joy? Are people with physical disabilities meant to be permanently confined at home? Is disability their crime — or a curse?

I dressed him in shirt and trousers, wrapped a sheet around his chest, and took him in the wheelchair to Motia Apa’s house. She came down from the second floor. Being out in the open air made him very happy. Every day he insisted on going out, but where could I take him? At most, the Parliament Building or Ramna Park.

Gradually, his entire right side became paralysed, then the left. I hired two people for physiotherapy and acupressure, alongside homeopathic treatment. The house was always full of people, solely to keep Tinku happy. He had a remarkable ability to adapt to adversity. With paralysis on both sides, unable to speak properly and barely able to see, he still tried to snap his fingers and dance to music just to make me smile. I pretended to be happy, but my heart was crushed with pain.

I knew his time was running out — very quickly. I no longer saw him as my lover, husband or friend, but like a small child: innocent, helpless, deeply precious. I felt an overwhelming urge to give everything of myself to keep him alive.

On 10 January, I was forced to admit him to LabAid. Then followed a month of nothing but waiting. I felt suffocated, desperate to run away — but I could not. I sat all day, staring at his face, losing track of days and nights. A feeding tube in his nose, an oxygen mask on his face, saline and injections through a central line in his chest — every moment filled with the fear that this might be the end.

In the end, everything ended.

At 7 a.m., he was sent to Anjuman Mufidul for the ritual washing, and I returned home. I locked the bathroom door, first removing my nose ring, then my bangles. I am a student of science, somewhat rational. Superstition had never held sway over me. Yet for the first time, I felt there was something deeply romantic bound up with the nose ring and bangles.

I asked for a white sari. My son asked, “Why white?”

“All colours — red, blue, yellow — exist equally within white. That is why it is considered pure,” I said. “It is symbolic — a mark of respect for your father. You should all wear white too.”

Tinku’s friend Sajjad Bhai said, “Distribute Tinku’s belongings among people. They will be useful to them. That is the custom.” I gave away his panjabis, trousers, shirts, ties and coats. But what about me?

We set off for Raozan. Suddenly, I saw the Anjuman Mufidul vehicle carrying Tinku. My chest tightened. Tears rolled down my face. My dearest person lay in an ice-cold van. I began to sob uncontrollably.

Raozan — Tinku’s dream village. How many dreams and hopes were tied to this place, all left unfulfilled. The first day I arrived here as a bride, many people came to see me. I had smiled shyly, adorned in jewellery, wearing a red sari. Today was the day of separation. Shame enveloped me more than ever before — the shame of helplessness, the shame of losing everything.

I put on a black burqa over my white sari. The first time, everyone had looked at my jewellery; today they looked again — but this time, finding nothing, someone finally said, “Take off the watch.” In our country, women are profoundly neglected and oppressed. Often, they seek their own satisfaction in another’s grief. I felt sorrow for that woman.

I studied at the University of Dhaka. I am the managing director of a brokerage house at the Dhaka Stock Exchange. Yet at this moment, beyond everything else, this remote village and its people felt deeply my own. I began to comfort them instead. Their love was what I needed most then. Like a beggar, I immersed myself in it.

I was utterly exhausted and fell asleep. When I woke, it was 4 o’clock. I thought of Tinku and began to cry aloud. Where has my heart’s jewel gone, my greatest treasure? After his illness was diagnosed, he used to say, “A time will come when you will search for me and not find me.” Now I search every moment — on the rooftop of Dolona Para, by the pond’s edge, behind the fields, in our bedroom. In what nameless land is he now? How is he?

Author: The wife of the late Jahangir Sattar Tinku

Gazipur Cantonment College has announced vacancies for three lectureship positions across different...

The Governor of the South African Reserve Bank (SARB), Lesetja Kganyago, has issued a stern warning...

In a surprising twist during the ongoing ICC T20 World Cup, former champions England found themselve...

In a significant administrative move, Bangladesh’s interim government has constituted a high-level c...

In a shocking incident in Mymensingh’s Bhaluka upazila, a 36-year-old housewife, Rahima Khatun, was...

Four members of the same family have been arrested in Jessore after a late-night joint security oper...

A fresh wave of violence has shaken the electoral contest in Jhenaidah-4, where the campaign office...

After months of uncertainty caused by visa complications, filming has finally commenced in India for...

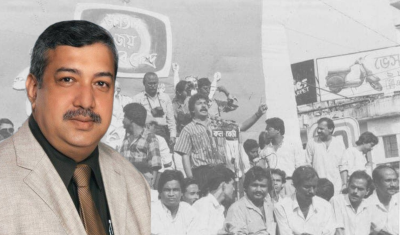

Jahangir Sattar Tinku’s life was a luminous blend of courage, intellect, and unwavering commitment t...

The Ministry of Cultural Affairs has initiated a hurried recruitment drive at the July Mass Uprising...

Bangladesh’s music enthusiasts are in for an exciting treat. Popular vocalist Shubho is set to relea...

On the eve of the 13th national parliamentary elections, the Bangladesh Election Commission (EC) has...